Lucía Mara / Here, There and Everywhere

May 18 to July 18, 2017

SOMEONE WHO WANDERS

Antonio Muñoz Molina

There are those who only see art in works of art; those who open their eyes professionally inside a gallery or museum but keep them shut otherwise. There are those who see art once it has been approved as worthy of admiration; those who see art not in the work but in the accompanying explanation, often written in a way that is preemptively artistic. If the explanation is in English, the words explore, boundary, uncharted, challenge, the Other, the gaze, etc, will abound. It is not a long list, but their combinatorial possibilities are very rich. Art is what people who call themselves artists make, and it is addressed to those with the authority to certify them as artists. Occasionally, in the best-case scenario, the recipients are speculators and plutocrats who buy, collect, and sell whatever has been credited as art by the dominant culture.

The result is a great boredom. A cloud of experts or initiates explains the work using the language described above, but the subject, if stripped of all explanation and witnessed alone, says nothing. Perhaps it has nothing to say. As Saul Bellow once said, this is an age full of explanations. In literature departments at universities books are less relevant than the explanations of the books. Solitary, sovereign reading is as rare as contemplating art without the accompanying jargon. You want to listen to the voice of the book, word by word, not that of its academic interpreter. You want to stand before a work of art and focus on what it is, what it’s made of, how. The work of art, like the book, must stand on its own, with undeniable firmness, with the confidence of what could not possibly be anything else. Pay close attention and you will also see how a work of art seems to float slightly above the ground; it is the weightlessness of a Paul Klee drawing, a field of color by Mark Rothko.

Over time I’ve discovered two antidotes against the tedium of the predictable, the self-absorbed, the artistic in art. One of them is photography. The other is what I would like to call “accidental art”.

The two are closely related. Photography continues to have its share of self-absorption and it is not immune to the temptation of the “artistic”, which comes from its very origins, when it sought to borrow the aesthetic legitimacy of painting (film once tried the same with theatre). But due to its very nature, its honest and immediate relation with the visible world, photography is in less danger of becoming a mere celebration of itself. Vanity is one of the most foolish passions, but also one of the most widespread, so we cannot assume that photographers are by nature immune to it. But the photographer, more than any other artist, embodies in her craft the discipline of observing what is happening in the world around her, the unexpected, the spontaneous, things of great significance to her but hardly under her control. Cyril Connolly writes that someone without love or curiosity for humanity is better served composing epigrams and maxims, instead of novels. Some of this applies to the realm of the visual arts. A great painter can be self-absorbed, a misanthrope, a hermit. A photographer must go out on the street and wander.

What I call accidental art is beauty that exists suddenly without anyone having to create it in a conscious manner, and many times without anyone even noticing it. It is a beauty that is as impersonal as the poetry of certain common expressions in language. Accidental art exists only in the moment of perception. And it leaves no trace, unless it is noticed and captured by photography. Accidental art is rarely overwhelming, exceptional or unusual. It is often so habitual, it becomes invisible. How many times have you seen, in New York or London, that warning on a sidewalk, accompanied by an arrow: LOOK? Suddenly, someone notices what has always been there, or discovers it as a newcomer to the city, and a word that is utilitarian and banal like any other traffic sign acquires a new meaning. It’s like a gong in a Zen monastery, an imperious call, a mandate to truly open your eyes once and for all, to get out of the robotic daze in which we’re so often submerged. Even those two Os confirm the sense: two eyes, round and wide-open, all we need to truly see.

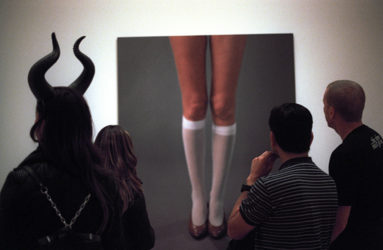

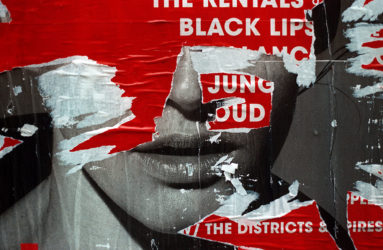

The natural space of accidental art is the city. There is a beautiful Spanish saying: the hare leaps out where you least expect it. The photographer, as a witness and practitioner of accidental art, knows the same is true of beauty, it leaps out where you least expect it, the spark of poetry, the “étincelle qui dure”, says Apollinaire, who knew so much about poetry and cities. Sometimes, wandering through the galleries in Chelsea, usually a disheartening experience, I have discovered the most powerful art not in what is labeled as such, but in the very architecture of the space, for instance, an old port warehouse with brick walls and iron beams, the print of an open hand on the pavement, a torn poster, the view of the river beyond a corner. In Chelsea, much more interesting than the walls of the galleries, I find the car-repair shops that remain, their red signs and bold colors, blues and yellows.

Even when I look at art that moves me, I try to remain attentive to the possibilities of the accidental. The sky grew light one morning after the rain, and the sun flooded the interior of a room already charged with the colors of a few Rothko paintings. I remembered how he detested bright artificial light, which nullified the natural radiance of the canvas. The morning light of New York was accentuated or softened inside that gallery, and the paintings were visibly changing. But the light also intensified the reflection of the painting on the polished floor, creating a corresponding, horizontal Rothko, like a tower of the Alhambra reflected on a pond.

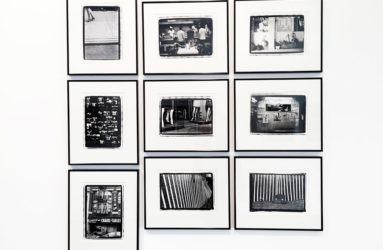

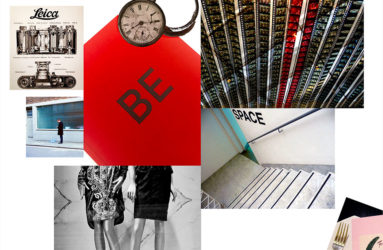

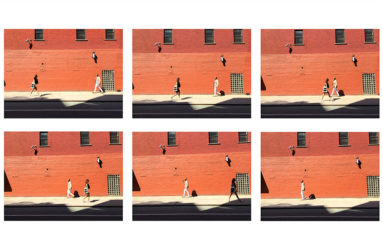

I have remembered that morning because I have seen one of Rothko’s paintings in a photograph by Lucia Mara. I have also seen a photo where light enters through the window of an empty room, most certainly in New York, and projects on the floor what could be called an accidental Rothko, a picture more fleeting but no less beautiful than the mandalas of colored sand created and destroyed by Tibetan artists. The immense lesson of photography is that the beautiful and the memorable are anywhere, and very often where no one is looking. Photography and the modern city were born at the same time. Nadar was Baudelaire’s contemporary, his friend, and the author of some of his most startling portraits. But Lucia Mara is more a disciple of Baudelaire than Nadar, mainly for a technical reason. The modern beauty that Baudelaire captured before anyone else, that of the solitary, curious and anonymous walker who simply wanders around, was not accessible to photography then, as cameras lacked speed and portability. I love to imagine Baudelaire with a Rolleiflex or a Leica hanging around his neck. In the center of his city, real and imaginary at the same time, Baudelaire locates the chiffonier, the junkman, the ragpicker: when Lucia wanders around the city and chooses a torn poster as the subject of a photograph, she is building on a tradition that dates farther than Walker Evans, and is more rooted in Baudelaire than Nadar. In the case of Lucia Mara, this genealogy takes a sudden turn, because her way of using color approximates painting; her reds are reminiscent of William Eggleston and Alex Katz.

The romantic invention of the idea of genius had the unpleasant consequence of favoring the often-hypertrophic egocentrism of artists, and the adulation and gullibility of the public. The photographer’s craft can be an antidote. Lucia Mara enjoys wandering in the freedom of anonymity, and that is what allows her to reduce her own presence to a minimum as she observes the world, like Baudelaire’s incognito prince. Her originality is not in an affectation as easily recognizable as the logo of a brand, but in something much more subtle, in the intensity with which she focuses on some things but not others; hers is not an arcane world but one that is full of light and for everyone to see. Even in a self-portrait she cautiously eludes the first plane of the self. It is seen in a window reflection, or in a shadow, like Vivian Maier, or in the face that is half-hidden by the great eye of the camera. It is she, and she alone, with her gaze, with her camera, in her time, in the cities that she knows. But it could also be anyone. That is the privilege of those who wander the city, and the photographer.

Translation Camilo A. Ramirez