In Praise of Shadows

The title of this exhibition is taken from the homonymous book by the Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki (Tokyo, 1886 – Yugawara, 1965) author of an extensive and celebrated narrative work. The first English translation of the book dates back to 1977. As luck would have it, on a short trip to Japan some thirty years ago, the person writing this now found that edition – by happy coincidence – in a Tokyo bookshop. Since then I have frequented this wonderful text in different translations.

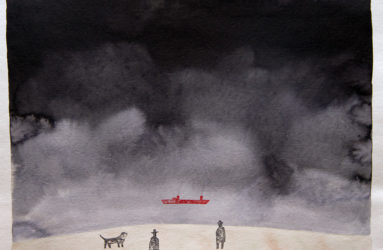

The most distinguished and appreciated in the French field has been that of René Sieffert, directly from Japanese. The one that has had more diffusion in Spanish is by Julia Escobar, who translated it from French and the publishing house, Siruela in Madrid published it (in 1994), with great success. Since that first reading, and the many that followed, I have thought about and imagined (rather fantasized about) an exhibition, which would pick up Tanizaki’s title and give an account of the shadow issue from a Western perspective. This project has finally been settled. Works by artists from the Gallery will be shown, who in their paintings and drawings represent the eternal light-shadow partition. Work very in accordance with this theme will also be seen from Argentine photographers of different generations.

Since I first saw Seascapes, photographs of seas from the 80s and 90s by the great Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, it was clear to me that if I ever carried out this project it would be desirable, and of poetic justice, to include them in it. The original editions of this large format series have reached a very high market price in these years. Luckily, more recently, smaller format editions and a more modest price have allowed the inclusion of one of these series in our exhibition. The photos by Sugimoto are in perfect harmony with Tanizaki’s inquiry, whose work, without a doubt, the photographer knows well, being himself an exegete of the traditional Japanese culture and a refined collector of his art.

Curiously, Tanizaki does not mention photography in his book. It could be conjectured that although there were prominent photographers before the 30s -date of composition of Elogio- the great expansion of Japanese photography is after those dates.

Our exhibition differs substantially from the uses of shadow expressed in Japanese aesthetics, which Tanizaki so acutely analyzes. There is a deliberation of the shadow that prevails in the West and that is situated just on the opposite side of the East. In the West, very different degrees and categories of shadow are distinguished, according to a greater or lesser incidence of light: darkness, gloom, umbra, dark opacity, chiaroscuro, etc. Likewise, Western art and architecture are turned towards the light; in traditional Japan the absolute value is the shadow.

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, shadow plays a practical and symbolic role, with specific ritual values sanctioned by time and custom. Light is its enemy, being at the same time a necessary complement.

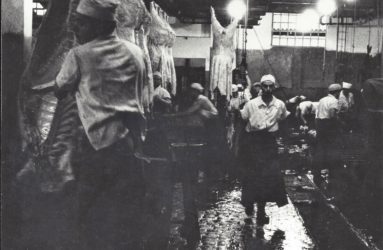

Light and shadow are antithetical values in permanent conflict, but essential for the existence of their opposite and between them the world is divided. Shadow – for Tanizaki- enhances the object or its surroundings, especially in architecture, providing ambiguity and mystery. Shadow ennobles the object and distinguishes it; is enigmatic, promotes silence and reflection, brings peace, serenity and calm. With a pleasant, colloquial, conversational style, Tanizaki displays his singular praise. His detailed and meticulous attention is fascinating. He subtly points out and analyzes the incidence of the punctual or diffuse shadow and its enemy, the violent light, both in art and in everyday objects. He describes and defends the choice of certain materials over others. Nothing escapes his observation and registration: from bathroom fixtures to kitchen (or surgical) utensils, from makeup and lighting in the theater to the traditional men and women´s clothes, everything is the object of his disquisition.

He defends and justifies, with ingenious arguments, the use of lacquer bowls, in which rice is eaten or soup is served, since these enhance the color and attenuate the weight of the food, if they are compared with the ceramic or porcelain, heavier and less opaque ones. Opacity is always a relevant value. The bright, refractory and burnished is scorned in favor of the matt, the patinated. In this time and use, the hand of man, contribute hierarchy and aesthetic value to the object. In Praise of Shadows abounds in multiple examples of this type. Tanizaki is an exceptional narrator – his novels and stories are testimony to these virtues – even in translation. This text is situated on a different plane, very different from that of his work of fiction, but shares with them a unique capacity for seduction. One of the greatest attractions of this book is, without doubt, the voice of the narrator, the tone of his story. It is about the inquiry of a poet, not that of a historian, an academic or an anthropologist.

The most recurrent shadow in figurative art and especially in photography is the image or two-dimensional silhouette, projected by a light source located behind an opaque object. There are many examples of the use of shadow in expressionist photography and in the “new vision”. Horacio Coppola, who trained in the Bauhaus and in the photographic modernity of the twenties and thirties, often used shadow very effectively and poetically in his photographs. Several examples of his work will be seen in this exhibition. Tanizaki does not refer to the projected shadow. His shadows are ambient, diffuse or punctual. (Perhaps this is one reason why photography is out of his registry). On the other hand, oriental painting, as well as western painting before the seventeenth century, rarely uses projected shadow. E. H. Gombrich analyzes the shadow projected in his text for the Shadows catalog, a fascinating exhibition that took place at the National Gallery in London in 1995.

In A Short History of the Shadow (1999) the Romanian historian Victor Stoichita makes a broad and erudite analysis of shadow in the history of Western art.

Jorge Mara