SurrealismoS

From April 24 to June 30, 2025

Aizenberg . Badii . Bengochea . Berni . Burton . Campanella . Coppola . Deira . Eguía . Forner . Maza . Kirin . Nojechowicz . Noé . Batlle Planas . Stern . Xul Solar

More than a movement with defined boundaries, Surrealism has been, since its inception, a zone of intensity: a way of seeing and transforming the world, rather than a style or a school. In his First Manifesto (1924), André Breton defined it as “pure psychic automatism,” emphasizing its roots in the unconscious, the instinctual, and the dreamlike. As we mark the centenary of that founding gesture, we aim to offer a perspective on Surrealism in Argentina, exploring how this movement manifested and transformed within our cultural context.

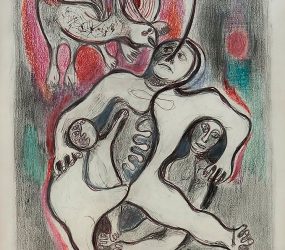

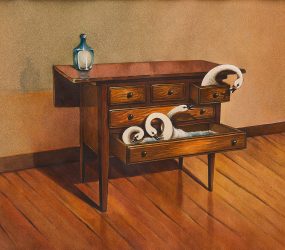

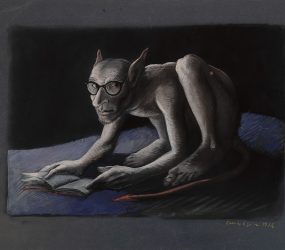

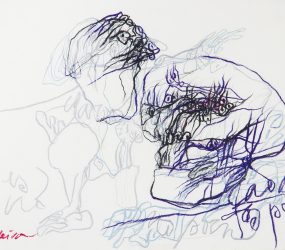

Many artists, without identifying as Surrealists or adhering to its dogmas, have ventured into its territories: into dream imagery, the logic of the irrational, coded eroticism, and the shadow of death. These dimensions compose a thanatic imaginary that has fueled modern and contemporary art in multiple forms.

In Argentina, Surrealism did not organize as a cohesive group, but rather as a transversal sensibility that took shape in a wide variety of works. SURREALISMOS proposes a journey through these offshoots: a discontinuous cartography built from tensions, affinities, and displacements. It does not aim to define a canon or fix an aesthetic, but to unfold a field of resonances.

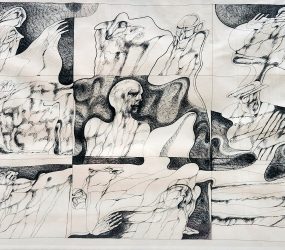

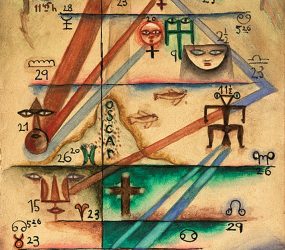

From the mystical systems of Xul Solar, where word, color, and symbol build an autonomous world, to Grete Stern’s photomontages, translating women’s dreams into unsettling allegories, Argentine Surrealism manifests as a force of rupture. Even before his Bauhaus training, Horacio Coppola had begun experimenting with fragmented images, abstract compositions, and optical games linked to a Surrealist sensibility. In Germany during the 1930s, he deepened this exploration through studies of light, reflection, and perspective that decomposed visible reality and reconfigured it from the threshold of the dreamlike. Juan Batlle Planas, in turn, translated inner drives into precise structures, where metaphysical and biological elements coexist.

In painting, Raquel Forner’s expressive intensity and Antonio Berni’s transfigured social critique reveal how the fantastic can also serve as an ethical response to historical time. Roberto Aizenberg and Vito Campanella approach form with obsessive rigor, constructing architectures of the unconscious—sealed worlds that evoke both dream and abyss.

The exhibition also includes works by artists whose practice engages with a material and symbolic Surrealism. With his enigmatic sculptures, Líbero Badii gives shape to the invisible; Fermín Eguía and Fernando Maza stretch the boundaries between figuration and abstraction to reveal latent zones of meaning. Miguel Bengochea, Kirin, Noe Nojechowicz, and Luis Felipe Noé trace other lines of escape, where gesture and symbol intertwine with the ritual, the political, and the lyrical.

Finally, the work of Mildred Burton, with its corrosive humor and encrypted eroticism, offers itself as a form of sabotage to common sense: a Surrealist path that dialogues with both the everyday and the monstrous.

It is important to highlight that Surrealism in Argentina is a living, ever-evolving current. The selection of artists presented in SURREALISMOS is but a glimpse within a broader panorama that includes both historical figures and contemporary creators exploring the dreamlike, the irrational, and the fantastic in their work. This exhibition, therefore, offers a specific perspective within a wider and more diverse movement that continues to inspire and challenge the boundaries of imagination.

SURREALISMOS is not a closed narrative. It is an open, vibrant map, where the oneiric, the instinctual, and the thanatic—beyond labels or movements—continue to operate as active forces in Argentine visual imagination.

Perhaps it is fitting—or at least amusing—to note that this text was created with the assistance of artificial intelligence. That is, with the help of an entity without a body, without dreams, and without an unconscious (at least for now), which has paradoxically contributed to shaping a text about Surrealism. What could be more surreal than that? A machine writing about the irrational. An artificial mind evoking the instinctual. One more piece of evidence—perhaps—that the real and the unreal can no longer be distinguished, or that logic, as Breton always suspected, is merely a bourgeois superstition.

Eugenio Ottolenghi

Thanks to an AI that does not dream—yet—but already writes.