HORACIO COPPOLA

Nocturnos

September 16, 2022 to February 28, 2023

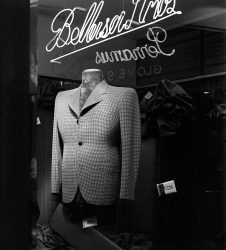

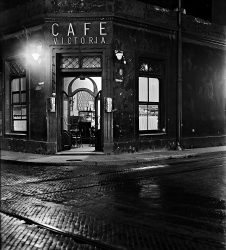

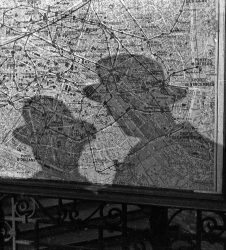

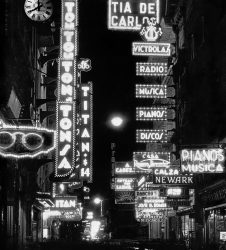

In – HORACIO COPPOLA – Nocturnos – we present a selection of photos by the Master himself from different periods and places, in which night, gloom or projected shadow, have a leading role.

From the beginning of his career, Horacio Coppola experimented with the contrasts of light and shadow in his images. There is a self-portrait from 1928 (when he was still using a camera borrowed from his brother Armando, his mentor and his first teacher) which is surprising due to its audacity and technical competence. A large part of Coppola’s photographic work is marked by the use of shadows, whether environmental or punctual. His nocturnal urban landscapes are comparable (in ambition and quality) to those of other famous photographers, cultivators of night photography, from the early decades of the twentieth century.

–

–

“Sometimes, things are there. You just have to know how to look”. H.C.

–

–

“I was born on July 31st, 1906, in my parents’ bedroom, on the 2nd floor of the house built in 1901, designed and run by my father: Corrientes, 3060. I began my life as the tenth member in the bosom of a family of adults. I was offered a plural initiation, and at the same time I learned to walk and talk, listen to music, grow plants and cut flowers, be a craftsman in the widest and most diverse handling of instruments, including, over time the camera, raise and live with birds and the most varied kinds of animals, read and write and manage newspapers and books and know the existence of languages: Genoese, Italian, French, in the framework of Creole exercises; mechanics, arts, science, literature. My home: an already fulfilled organized world”. H.C.

–

–

Nocturne refers to certain artistic genres (pictorial, musical, literary, photographic) which initially only defined, in painting, those scenes set at night. In ancient art, before the seventeenth century, for technical or symbolic reasons, such scenes were not frequent. In the Renaissance some artists used chiaroscuro masterfully (Leonardo Da Vinci, for example). In Baroque painting Caravaggio and his followers (called Caravaggists or Tenebrists) adopted methods of violent light / shadow contrasts in order to accentuate the drama of their works; others, like Georges de La Tour, used original and ingenious ways (with candlelight, for example) to illuminate their characters. Rembrandt, Velázquez, Zurbarán, Vermeer and various other painters of that time masterfully used the contrasts of light. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there were artists who continued and innovated in the use of light/shadow antagonism in visual arts. One of them, James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) made night and shadows the main subject of a substantial part of his exquisite pictorial work. We owe him the name “nocturne”, with which he baptized several of his paintings. The name was extended to music, poetry and, of course, to photography, to which his work contributed so much. Whistler was born in North America, but his life was spent almost entirely between London and Paris. His first incursion into nocturnal painting was Nocturne: Blue and Gold, Valparaíso (1866-1874), which he painted on a strange trip to the port city to which he travelled – mysteriously – with the objective of helping Chile in the war against Spain. One of his most famous and emblematic works belongs to this period: Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge, a view of the Thames focused on the presence of water, its reflections and those of some fireworks that descend from the sky with the Battersea Bridge dominating the pictorial surface and a boat and its oarsman passing below. The work is singular and enigmatic. It was very controversial and gave people a lot to talk about at that time. Whistler was not only an original and influential artist, he was also admired by relevant writers of his time: Mallarmé, Huysmans, Proust, Wilde – first his friend and later his enemy – with whom he competed in wit and arrogance.

To mention just a few famous photographers, cultivators of the night photo: Stieglitz, Coburn and Steichen wonderfully photographed the streets of New York. Paul Martin – Alsatian by birth, Londoner by residence – photographed London under street gas lamps with subtle poetry, André Kertész (Budapest, 1894 – New York, 1895) first and Brassai – pseudonym of Gyula Alász – (Hungary, 1899 – France 1984), immediately afterwards, both documented Paris at night supremely. It is with Brassai that Coppola has his greatest affinity. The likeness of their images is often striking. In the 1930s, when Brassai took most of his Parisian photos, it is unlikely that the Argentine photographer was aware of Brassai’s work. The latter published his famous book, Paris de Nuit, in 1932. Coppola then lived in Berlin and participated in the Bauhaus until it closed in 1933. There was, presumably, no point of contact between the two photographers. There are common themes in modern photography ,topics that avant-garde photographers adopted and explored. This is true amongst many artists who coincided in the art schools of the time (the Bauhaus, for example) or belonged to the same movements (New Vision, Expressionism and New Objectivity to name a few). In Coppola there are traces of these artistic currents, but not so in Brassai. During the 1930s, the Hungarian-French photographer produced a photographic series on “graffiti,” the signs, graphs, and drawings incised on the walls of Paris. Coppola, also around this time, in 1933, photographed various graffiti, first in Paris and later, in 1935, in London. The likeness is amazing. We know that Coppola and Brassai did not know each other, and given the simultaneity in the dates of their works and their cities of residence, it is highly unlikely that they were aware of their mutual work. Brassai worked on this theme with fascination, Coppola incidentally. Both photographers shared more than one interest. Not long ago a celebrated French critic, curator and Brassai specialist named Agnès Gouvion de Saint-Cyr (author, amongst other things, of a book: Brassai, pour L’amour de Paris) visited our gallery and carefully studied Coppola´s photos, which she knew superficially. Her surprise at the similarity of the work from both artists was immense. She had written, exhibited and researched Brassai’s “graffiti” and could not explain the formal similarities and the synchrony between the series.

J.M.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I want to thank my friend Lily Litvak, critic, historian, author of numerous books and articles on art, literature, history of ideas, professor emeritus at the University of Texas, specialist in European and American Modernism (South and North), curator of exhibitions, great connoisseur of the Spanish art and literature from the eight hundreds, erudite, possessor of extensive and multiple knowledge; the references to James McNeill Whistler were taken from her masterly essay: Nocturne: Blue and Gold-Old Battersea Bridge. From Night Painting to Photography. From Nocturne: Blue and Gold to Steichen’s Flatiron.